Franz Josef’s Carriage

For fifty years, Western Costume owned one of Austrian Emperor Franz Josef’s royal carriages. The carriage, along with boatloads of other Austrian relics, was brought to Los Angeles in the 1920s for an Erich von Stroheim film. Some of these Habsburg artifacts are still in Western’s collection ninety years later, having appeared in countless films; the ultimate fate of the carriage, though, is a mystery.

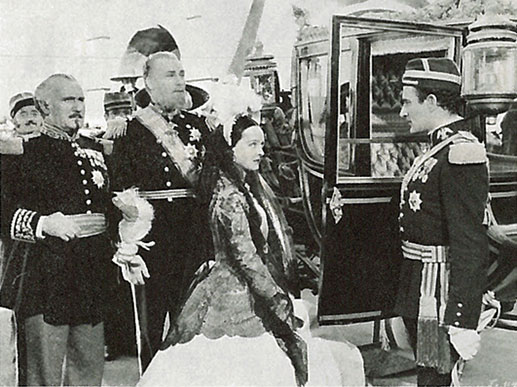

A scene from Erich von Stroheim’s The Wedding March (1928).

Born of director Erich von Stroheim’s homesickness for his native Austria, The Wedding March (1928) memorialized the magic of Vienna before the first World War. Von Stroheim was known for his insistence on “ruthless realism” in his films. He went so far as to hire Archduke Leopold, grand-nephew of Emperor Franz Josef, as a consultant on the film. “Stroheim,” recalled Archduke Leopold, “was anxious to get a favorable judgment about this part of the film from a member of the Imperial House.” The legendary director’s insistence that every detail of the film look exactly like his memory of Vienna required going to great lengths—and great expense: he went half a million dollars over his $700,000 budget!

Western Costume Co. proved instrumental in securing many of the authentic relics seen in the film. In the early days of Hollywood, the costume house provided props and set dressing in addition to costumes. A Western Costume employee, William House, recalled in a 1938 issue of Silver Screen, “One of our buyers went to Vienna and brought over two royal carriages, costly furs, medals and insignia, court, diplomatic, civil and military uniforms. Among the uniforms there was a coat worn by Emperor Franz Josef. It was one of the most valuable purchases we have made.”

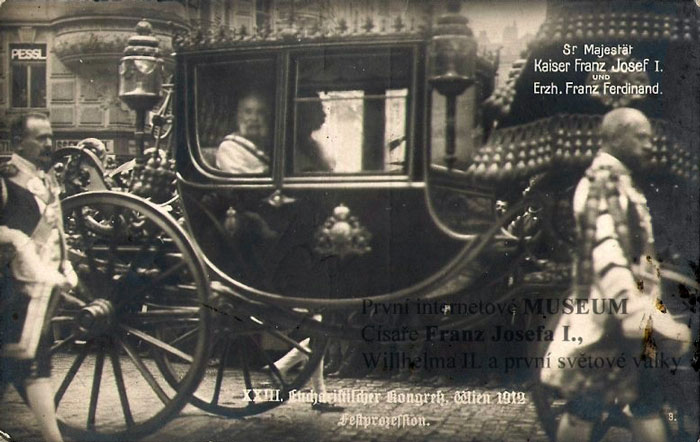

Franz Josef rides in his dress carriage, 1912.

In 1928 Western Costume Research Director Edward Lambert (my predecessor) told Photoplay: “More than just a faint breath of a national sensation was created when the royal carriage of the late Emperor Franz Josef was literally yanked out of the Vienna Museum.” The carriage in question was a gilt, Armbruster dress chariot made in the middle of the 19th century. “Along with it,” Lambert continued, “came the royal coat of arms, the actual uniforms and equipment worn by the Emperor’s coachmen, lackies, footmen, and postillions, as well as the matchless harness of the eight horses which drew the carriage. These things were acquired by an European representative of the company under somewhat strenuous circumstances.”

Erich von Stroheim as Nicki in The Wedding March.

The uniforms, like the props, were brought from Vienna. “Von has assembled everything necessary to make this picture one of the masterpieces of realism for which he is famous,” stated a 1926 blurb in Motion Picture Classic. “Authentic uniforms, which formerly adorned the officers of the Austrian army, were purchased and imported and now lie folded in a mighty heap in the wardrobe room […] Decorations of every kind, purchased from pawn-brokers and collectors, have been assembled to deck the bosoms of the gentlemen who will compose the von Stroheim army corps.” So authentic were the uniforms, Western employee House recalled, “I pulled out a coat from our Vienna lot and gave it to [an extra of Austrian descent]. He scrutinized it for a moment, and said, ‘That’s mine.’ He looked at the rag, and read his own name on it. He felt in his trembling fingers the four medals hanging on the breast. They were his too. Then he turned around to hide his face, and started crying.”

Ultimately all of the work and expense that went into making The Wedding March was worth it to von Stroheim. When he walked through one of the 36 meticulously created sets, he is said to have exclaimed, “It is Vienna. Vienna, before the great war of 1914—Vienna the melodious, the romantic, the dramatic—my Vienna!”

After filming was completed, all the pieces that Western Costume Co. had purchased for the film were incorporated into their rental stock. “They now repose on the second floor of this building,” Lambert explained in 1928. A decade later, Western Costume President J. L. Schnitzer claimed that, thanks to this acquisition, his company had “more original and genuine uniforms of the Austro-Hungarian Empire than you can find in Vienna.” The uniforms and Habsburg antiques were used in many subsequent films.

Ronald Colman and Madeleine Carroll in The Prisoner of Zenda (1937).

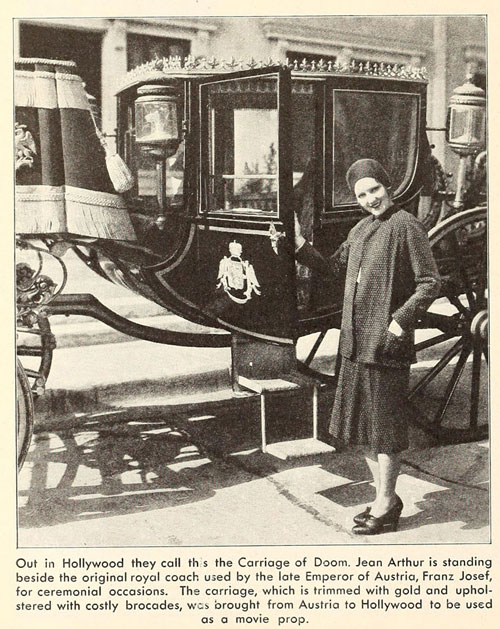

Bette Davis prepares to board Franz Josef’s carriage in Juarez (1939).

The Armbruster carriage can be seen in The Prisoner of Zenda (1937) and Juarez (1939). For the The Prisoner of Zenda, certain modifications were made, including the addition of a large golden ornament to the top of the carriage that can still be seen in Juarez and in the much later photo of the carriage (circa 1980s?) below.

Western Costume’s Carriage in the 1980s

Austrian medals from the Western Costume collection.

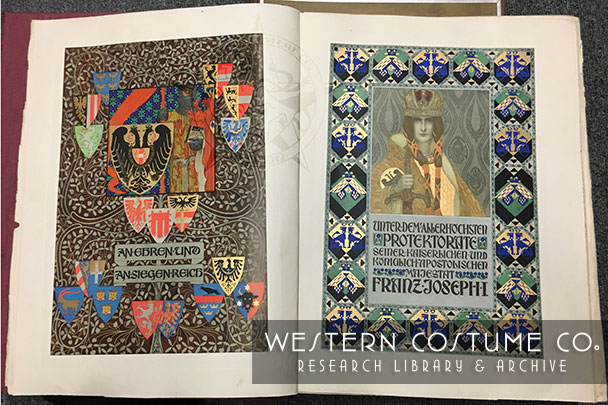

In the decades that followed, many of these treasures were either sold or simply disappeared. For example, when Western Costume moved from Melrose Ave. to North Hollywood in 1990, only two original Austro-Hungarian swords were spotted among the 3000 swords in the collection; they sold their entire weapon collection a few years later. The research library still holds numerous books that were undoubtedly a part of the Viennese acquisition, including several turn-of-the-century, art nouveau volumes. In addition, Western still possesses many of the medals purchased for the film.

[WCC Collection]

[WCC Collection]

I had hoped to trace what became of the dress carriage, but every piece of information I found left me more uncertain. In the mid-1990s, historic carriage collector Gloria Austin purchased an Armbruster carriage from “a Hollywood film studio” (although another article says that she bought it from a carriage restorer in Oregon). She hired a Belgian restorer, Patrick Schroven, to restore it to his original splendor. According to Austin, Schroven spent 10 months researching before beginning the task, and ultimately enlisted 60 expert craftspeople from across Europe, including “a metal-turner, a wheelwright, a wood-turner, a smith, a wood-sculptor, an iron-founder, a copper-founder, a gilder, an ivory cutter, a cane-weaver, a glass-turner, a patternmaker, a chaser, a braid-maker, a gold-embroiderer, a saddler, a passmentrymaker [sic], a fabric-weaver, a tailor, a wigmaker, a whip-maker, a button-maker, a hatter, a lace-maker, a gold-leaf expert, a lamp-maker.” The beautifully restored chariot now resides at the Florida Carriage Museum, and is the only full-state carriage in the US.

Armbruster dress coach at the Florida Carriage Museum.

I initially assumed that carriage in the Florida Carriage Museum was the one that Western brought over from Vienna in the 1920s, and, in fact, the museum claims that their carriage appeared in Juarez. I’ve spent months trying to confirm, but have had trouble getting in touch with either the museum or Gloria Austin. This past week, I came across a photo of the Gloria Austin carriage before it was restored that makes me question whether it was the one Western owned. The photo on the left shows the Western Costume carriage in, I believe, the 1980s; the photo on the right is the Gloria Austin carriage in 1998. You can see that the Western Costume carriage, while in much better condition, is missing its front lamps. Even if the gold decorations were removed and the paint was scratched off in the intervening decade, it seems unlikely that the lamps were somehow added back before the 1998 photo was taken.

Western Costume’s carriage, circa 1980s. [WCC Collection]

Austin’s carriage before restoration, 1998. [Photo courtesy of Patrick Schroven.]

[From The New Movie Magazine, April 1930.]

Trying to discern truth from vintage movie magazines is nearly impossible. William House recalled two carriages being brought over, but Edward Lambert only mentioned one. Most references I found claim that the carriage and Viennese artifacts were brought over for The Wedding March. However, I have found three references that say they were brought over in 1922 for a von Stroheim-turned-Rupert Julian film called Merry-Go-Round (1923). One of these articles explains that “immense quantities of actual uniforms and accouterments have been purchased in Vienna and have arrived at Universal City, together with Emperor Franz Josef’s carriage, which was secured after three months’ negotiations with the Vienna authorities.” An article about Juarez says the carriage was brought over for yet another von Stroheim picture, The Merry Widow (1925). And still another version of the story, from a docent at the Carriage Museum in Florida, says that Maximilian, brother of Franz Josef and brief Emperor of Mexico, brought the carriage over when he took the Mexican throne in 1864, and that it eventually made its way to Hollywood.

Some articles claim that the shipments were brought (and subsequently owned) by Universal, yet others say Western Costume. A 1922 New York Times article states that Universal rented one of Franz Josef’s carriages for Merry-Go-Round, and when the time came to return it, Viennese authorities “told Carl Laemmle to keep [it], as the freightage would eat up whatever rental profits the community would receive.”

Were people simply mixing up which Austrian film the antiques were initially purchased for? Did Western own the carriage or did Universal? Could the discrepancies in the articles and mysterious missing headlamps mean there were two Armbruster dress carriages?

If so, perhaps the Universal carriage (or one that came via Maximilian and Mexico?) is the one that Gloria Austin purchased and that now resides, immaculately restored, in Florida. The Western Costume carriage—with its strange crown topper—was clearly the carriage in The Prisoner of Zenda and Juarez. But if it is not the same carriage that Gloria Austin bought in the 1990s, what happened to it?

Sources:

“Abandon Emperor’s Carriage.” Los Angeles Times. October 21, 1923.

Archduke Leopold, “A Habsburg Sees Hollywood.” Photoplay. May 1928.

Campbell, Ramsey. “Arriving in Grand Style.” Orlando Sentinel. December 22, 2000.

“Full Particulars of Universal’s Product for Coming Year.” Universal Weekly. July 15, 1922. Pg. 15.

“Golden Carriage of the Austrian Emperor in Florida – Gloria Austin.”Horse and Carriage Facts. 2015. Web. 29 Jan. 2016.

Howe, Herb. “C’est Mon Homme.” The New Movie Magazine. April 1930. Pg. 118.

Jopp, Fred Gilman. “The Ask Me Another Man.” Photoplay. February 1928.

“Juarez.” Photoplay. June 1939.

Koszarski, Richard. Von: The Life and Films of Erich von Stroheim. New York: Limelight Edition, 2004.

“‘Merry-Go-Round’ the Title of New Stroheim Production.” Universal Weekly. June 24, 1922. Pg. 34.

“Old Pre-War Vienna Reproduced in Film.” New York Times. January 2, 1927.

“Production Difficulties.” New York Times. July 22, 1923. Pg. X2.

Ryan, Don. “The Screen Observer Has His Say.” Motion Picture Classic. August 1926.

Schumer, Tracy. “Lady Weirsdale.” Web log post. High Minded Horseman. N.p., 11 July 2010. Web. 28 Jan. 2016.

Surmelian, Leon. “Off the Beaten Track.” Silver Screen. March 1938.

“The Wedding March.” Los Angeles Times. August 15, 1926.

“Von Stroheim’s New Film.” New York Times. January 8, 1928.

Tags: 1920s, Erich von Stroheim, Hollywood history, props, The Wedding March, uniforms, WCC History

Trackback from your site.

Josh

| #

Well researched and well written. This was definitely worth reading and I feel jealous that I lack the access and drive you have!

Reply

Susan Honig-Rogers

| #

Is it possible that the lamps were merely removed from the carriage for transport or storage, as they likely stood out from the main body in a way that might make them subject to damage? Your picture of Western Costume’s carriage in the red truck seems to show a damaged remnant of a front lamp in place.

Reply

Leighton

| #

Definitely a possibility, but why remove only the front lamps?. I wish I could get in touch with the woman who bought it. I think, though, that what you are seeing that look like remnants of the lamps are actually the plaster “drapes,” for lack of a better word, that were added for Zenda. There are other curious differences between the photos, but mostly those come down to elements that appear in the earlier photo not appearing in the later photo. Age could account for that. The lamp just stuck out because it is something that isn’t in the earlier photo and IS in the later photo. The upholstery is also different in the 2 photos. I’m going to send the link to the restorer and see if he can shed any more light on it.

Reply